By Nightwatchman (and his brother).

By Nightwatchman (and his brother). Cricket is the cornerstone of the inclusive English society in our green and (mostly) pleasant land.

While our European brethren were at loggerheads with their various social estates the English were busy gelling their social relationships with squire, farmer, clergy and blacksmith working as a team doing noble battle on the cricket green. The Village Green was the scene of a (very British) revolutionary classless society playing to the strengths of the artisan and gentry and forging a unique sense of identity and community.

.

Our national great game with its roots in ancient rural gatherings became the social glue in the 18th century that prevented heads rolling and bands of marauding brigands causing mayhem and anarchy.

Our national great game with its roots in ancient rural gatherings became the social glue in the 18th century that prevented heads rolling and bands of marauding brigands causing mayhem and anarchy.

.

Although this idyllic picture may seem far-fetched, it is clear that further historical investigation points to a true picture of social cohesion. On the eve of the French revolution a team of South Eastern county cricketers led by a local dignitary was bound for France only to be sent back after the local populace would not entertain members of the three estates working in such obvious harmony.

Although this idyllic picture may seem far-fetched, it is clear that further historical investigation points to a true picture of social cohesion. On the eve of the French revolution a team of South Eastern county cricketers led by a local dignitary was bound for France only to be sent back after the local populace would not entertain members of the three estates working in such obvious harmony.

.

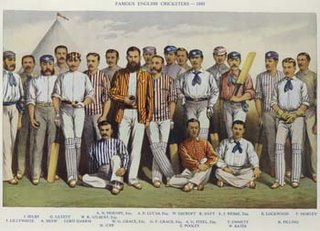

This state of affairs had its limits as shown by the existance of separate changing rooms up to the 1950s for gentleman and players. However the autocratic toff Douglas Jardine (actually a Scot) could rely on the coal mining artisan Harold Larwood to obey orders and bodyline Bradman out of the Ashes rubber of 1933/4 (the gentleman Gubby Allen refused and was dropped from the test team).

This state of affairs had its limits as shown by the existance of separate changing rooms up to the 1950s for gentleman and players. However the autocratic toff Douglas Jardine (actually a Scot) could rely on the coal mining artisan Harold Larwood to obey orders and bodyline Bradman out of the Ashes rubber of 1933/4 (the gentleman Gubby Allen refused and was dropped from the test team).

However the rules of engagement which were appropriate to the social etiquette of the times ensured that social harmony could take place and allowed the essentially English nature of the game to foster the working together of the separate classes and to reflect a microcosm of the society in which they lived. This is absent from the ex-colonial cricket playing nations whose domestic and international game has been rife with schisms and divides on racial and class divides.

So it came to pass in the glorious summer of 2005, the dulcet public school tones of BBC commentator Christopher Martin Jenkins rejoicing in the achievements of the artisans Flintoff and Harmison with a little help from some colonial farmhands Pieterson and Straus to deliver the ashes back to good old Blighty and safe from the ex-convict mono class Aussies.

.

Howzat, sir.

1 comment:

Yes and the ladies, in floppy hats, made those nice cucumber sandwiches (no crusts of course) on those glorious days of summer.

Lest we forget.

Post a Comment